In March 2009, David Tepper bought Bank of America near $3.14 and Citigroup near $0.97.

Everyone else was running for the exits.

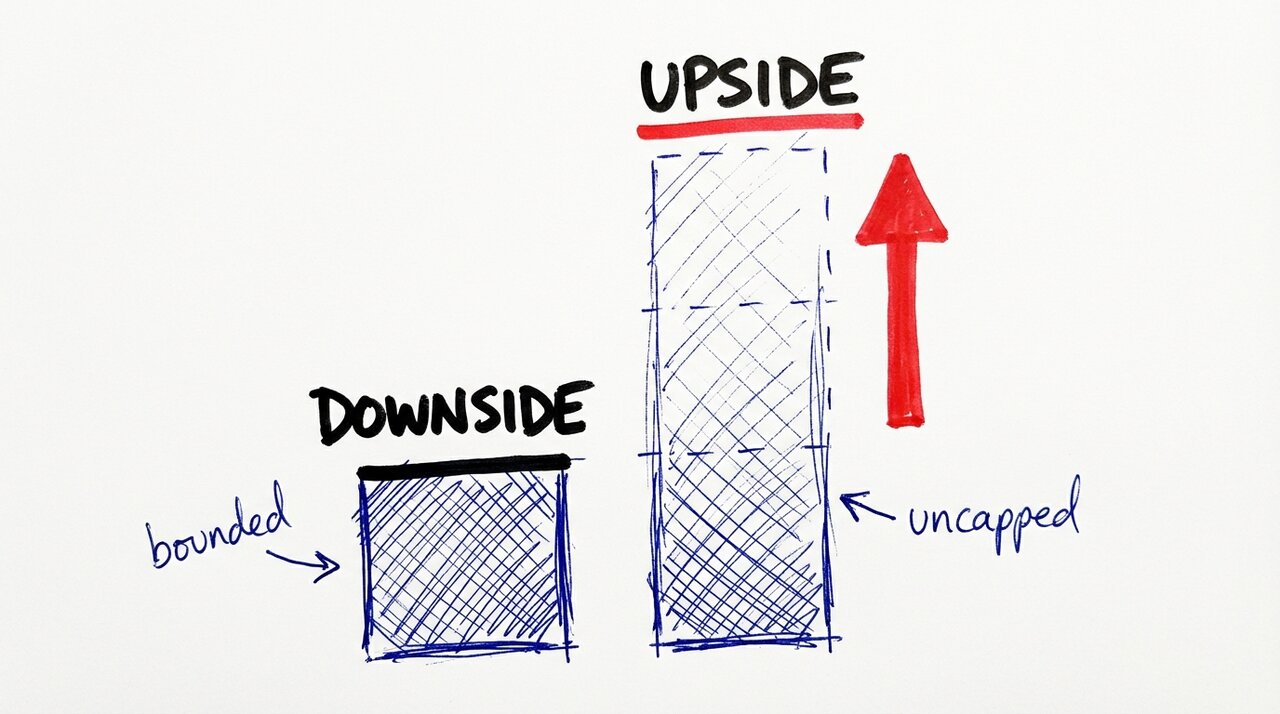

Tepper saw it differently. He’d spent years doing distressed credit analysis. He understood bank balance sheets at a granular level. And he understood something the panicking masses didn’t: the government had backstopped the system. The downside was priced in. The upside wasn’t.

That year, his fund returned 133%. $7.5 billion in profit.

This is what an asymmetric bet looks like: bounded downside, uncapped upside, grounded in knowledge others don’t have or won’t act on.

Job Risk vs. Career Risk

We’re trained to optimize for looking smart at every step. This conditioning creates a dangerous confusion: we conflate job risk with career risk.

Job risk is losing your current role, income, or immediate reputation. Your manager thinks you’re unfocused. Your LinkedIn looks “weird” for 18 months.

Career risk is spending 10-20 years on a track where you become interchangeable with thousands of others, where your upside is structurally capped, where you miss compounding exposure to domains that later become huge.

The paradox: many “safest” jobs carry high career risk if the world is changing quickly.

Kyle Samani was unemployed at 26. He could have taken the respectable path. Instead, he dove into crypto in 2015-2016, when most VCs had explicit policies against touching it.

From a job perspective, this looked terrible.

From a career perspective? He was accumulating non-replicable knowledge in a frontier domain. He founded Multicoin Capital. The domain exploded. The “weird” choice became the obvious choice, in retrospect.

Here’s the thing about asymmetric bets: before you look brilliant, you almost always look stupid to someone whose opinion you care about.

The Asymmetry Equation

A simple mental model:

Weird × TAM × Edge = Asymmetric Opportunity

All three terms matter.

Weird: Non-Consensus Belief

“Weird” means non-consensus. Not random eccentricity. A genuine belief about how things work that most people don’t share.

Peter Thiel’s famous question captures it: “What important truth do you believe that very few people agree with?”

The payoff only exists when the market hasn’t fully priced this belief in yet.

TAM: The Size of the Outcome Space

If this works, how big can it be?

Consider three businesses earning the same $1M/year:

- 1 user paying $1M/year

- 10 users paying $10K/month

- 1,000 users paying $100/month

The first is fragile and maxed out. The third could 10x or 100x with the same model. Same revenue today. Wildly different ceilings.

Ray Kroc saw this clearly. When he bought out the McDonald brothers, the restaurant was already successful. But Kroc wasn’t buying a burger joint. He was buying a system that could scale to every highway exit in America. The TAM wasn’t “one good restaurant.” It was “every family that eats out, everywhere.” Bounded capital per site. Uncapped expansion.

Edge: Unique Knowledge

Without edge, you’re buying a lottery ticket.

Edge is your structural advantage: information others don’t have, skills others can’t match, risk tolerance others won’t adopt.

Tepper’s 2009 bank bet wasn’t courage. It was years of distressed credit analysis. Deep understanding of how TARP would flow through the system. He wasn’t guessing. He was reading regulatory filings while everyone else was reacting to headlines.

The practical test: What can I see or do that an equally smart stranger couldn’t replicate in 6-12 months?

If you can’t answer that, downsize the bet or spend time building edge.

The Equation in Action: Bill Perkins

Some people apply this framework once. Bill Perkins has built his entire life around it.

In 1991, Perkins took a bottom-rung job as a trainee clerk on the floor of the New York Mercantile Exchange. Not a blue-chip analyst seat. Shouting orders in the pits. But it was a front-row view of how energy markets actually worked.

By 1995, he’d left New York for Houston to trade derivatives during the deregulation of the Texas electricity market. Weird: a volatile niche most people avoided. TAM: electricity and natural gas are among the largest markets in the world. Edge: quantitative chops plus day-to-day exposure to physical and derivatives flows that few traditional finance people had.

In 2006, Amaranth Advisors imploded, losing roughly $6 billion on leveraged natural gas bets. Perkins, then at Centaurus Energy, helped take the other side of those positions. The trade looked insane until Amaranth broke. Then it paid off on a scale that made headlines.

He wasn’t guessing. Centaurus had built a deep fundamental view of gas supply, storage constraints, and seasonality. When Amaranth’s positions became crowded and mispriced, Perkins was willing to be the liquidity provider into a panicked market.

After Centaurus shut down in 2012, he founded Skylar Capital. Same playbook: concentrated bets in natural gas and power markets. The fund returned +227% in 2015, +107% in 2021, and roughly +208% in 2022 (one of the top hedge fund performances globally that year). Also significant drawdowns: -54% in 2013, losses in 2017, 2018, 2020.

Extremely lumpy. Precisely what you’d expect from asymmetric, high-conviction bets in a fat-tailed market.

Then he did it again in a completely different domain.

SynMax uses satellite imagery and AI to monitor oil and gas assets, track production, and provide energy intelligence. SkyFi democratizes satellite data, letting anyone order Earth observation imagery with transparent pricing. Both companies sit at the intersection of two things Perkins knows cold: the value of small information edges in energy trading, and the explosion of underutilized satellite data.

He even wrote a book applying the same logic to life itself. Die With Zero argues that conventional “save and hoard” financial advice optimizes for the wrong thing. The real objective isn’t maximum terminal net worth. It’s maximum lived experience. Pull forward experiences when you’re young and healthy. The marginal utility of money at 80 is far lower than at 30.

Weird? Absolutely. Most financial advisors would call it reckless. But it’s a testable, actionable belief that leads to radically different life decisions.

Same pattern, different domains: energy trading, hedge funds, satellite companies, life philosophy. Weird × TAM × Edge, repeated.

The Hidden Costs

The math on asymmetric bets is often fine. What kills people is how it feels while it’s not working.

Most ambitious professionals overestimate identity risk and underestimate recoverability. They’re not afraid of being broke. They’re afraid of being visibly wrong.

01 On Bet Sizing

Even positive expected value bets can be catastrophic if sized incorrectly. The core rule: never take a career bet where failure threatens your ability to keep playing.

A simple framework, riffing on the Kelly criterion: the Personal Kelly Fraction.

5-10%: Experiments. Side projects, small angel checks, 3-6 month tests. Recon missions.

20-40%: Serious but survivable. Lower salary for equity. Joining an early startup. Switching fields. You’ll feel it if it fails, but you’ll recover.

50%+: Only with genuine edge. Founding a company in a space you’ve operated in for years. These require conviction backed by unfair advantages.

The Age Question

“Am I too old for this?”

It’s the question lurking behind every conversation about asymmetric bets. And the answer is: it depends, but probably not.

Think about how investment advisors talk about portfolio allocation. Young investors get told to go aggressive: 90% equities, ride the volatility. As you age, you shift toward bonds and stability because you need predictability, you have less time to recover from drawdowns, and you’re drawing down rather than accumulating.

Career bets work the same way. The variables that matter are runway, obligations, and recovery time.

At 24, with no mortgage and no kids, $10,000 in savings might represent 12 months of runway to take a swing. That same $10,000 at 42, with a family and a mortgage, barely covers a month. The absolute dollars didn’t change. Your circumstances did.

This doesn’t mean you stop taking asymmetric bets. It means you size them differently.

02 The Side Bet

If your main career can’t absorb volatility, your side projects can. A weekend project with asymmetric upside is still an asymmetric bet. You don’t need to quit your job to play.

A 45-year-old VP with two kids in private school probably shouldn’t quit to bootstrap a startup with no revenue. But that same person could:

- Angel invest 5% of their net worth in founders they have edge on

- Build a side project in a domain where they have decades of expertise

- Negotiate equity in a late-stage startup while keeping their salary

- Advise early companies for equity in exchange for their network and knowledge

The bets get smaller. The edge often gets bigger. Two decades of industry knowledge is genuine alpha if deployed correctly.

Build Your Runway Early

Here’s the move most people miss: the best time to create optionality is before you need it.

If you’re 25 and earning $80K at a safe job, aggressively investing that income might feel boring. It’s not. You’re buying future runway.

An extra $50,000 invested in your late twenties becomes $200,000+ by your late thirties (assuming 7% real returns). That’s not retirement money. It’s freedom money. The difference between “I can’t afford to try” and “I can survive 18 months of zero income while I figure this out.”

Wealth makes career risk easier to absorb. Not because rich people are smarter or braver, but because they can survive longer while a bet plays out.

The practical implication: if you’re in an early career safe job, don’t just optimize for title and salary. Optimize for savings rate. Build the cushion that lets Future You take swings.

I’d argue that aggressively investing income from one of those early jobs to establish financial independence is one of the best strategies before starting a company. It lets you bootstrap without desperation. It means you can raise a small seed from friends and family instead of giving up half your company to VCs because you needed the money yesterday.

The goal isn’t to hoard wealth forever. It’s to build enough that you can afford to be patient, take smaller checks, keep more ownership, and wait for the right opportunities instead of grabbing whatever’s in front of you.

Compensation Structure as Leverage

If you can’t change the game, change how you participate.

Mario Lemieux was owed $26 million in deferred salary by the bankrupt Pittsburgh Penguins. The conventional move: fight for cash in bankruptcy, get cents on the dollar.

Lemieux converted that unpaid salary into equity. Became majority owner.

The Penguins drafted Sidney Crosby. Won three Stanley Cups. The franchise value exploded to over $1.7 billion. Lemieux’s stake: reportedly $350 million when he sold.

He didn’t change the game. He changed his participation rule.

Think of compensation structures as call options: lower salary now for the right to participate in large upside later. Equity grants, early-employee options, carried interest, revenue share.

The question isn’t “how much am I getting paid?”

It’s “what’s my participation rule in the system’s payoff?”

Choosing Your Weird

The Barbell Strategy: keep one side safe (stable income, generic skills). Load the other side with wild asymmetry (high-variance projects, unusual investments).

The middle, mildly risky with capped upside, is the least attractive position.

Before you act, answer three questions:

-

What do you believe that your smart friends don’t? Not what sounds contrarian. What would you actually bet on?

-

What’s the TAM if you’re right? A weird belief about a tiny niche might be correct but not worth your time. “Big enough” is personal: $50K/year changes one life, $5M changes a family’s trajectory, $500M builds an institution. Know which game you’re playing.

-

Where’s your edge? If you can’t articulate it, you’re not ready to size up.

The market doesn’t care that you never looked stupid. It only cares whether you’re rare and valuable when things change.

The math favors the contrarians who do the work.