When you’re at the starting line of a new idea, you have almost nothing concrete. A vague pattern. A hunch. Maybe a mental image of something that could exist. That’s not a weakness. It’s the only way exploration begins.

Most of us stall here. We wait for validation, for proof, for a clear path forward. But proof comes late. The messy, uncertain beginning is where the real work happens. And increasingly, I think AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, or Amp can help us navigate this fog.

This is a guide for engineers and creative technologists who want to explore ideas more systematically, without killing them prematurely.

The Starting Line Problem

Engineers are trained to value evidence and reproducibility. Early ideas have neither. This creates an uncomfortable tension: you can’t answer basic questions yet. Who is this for? What’s the exact problem? How does it work at scale?

Any comparison to “real” products makes your half-formed idea look silly. The more technical knowledge you have, the easier it is to generate reasons the idea will fail. You know too much about all the ways things break.

Here’s the trap: if you demand proof too early, everything looks like a bad bet. You never leave the starting line.

The problem isn’t lack of discipline or talent. It’s using late-stage evaluation criteria on early-stage ideas. Day 0 needs different tools than Day 100.

Trusting Your Inner Voice

At the beginning, intuition is the only signal you have. I don’t mean intuition as mystical insight. I mean it as compressed pattern recognition built from years of building and debugging. Your brain’s cached gradients from real experience.

Early conviction doesn’t mean “this will change the world.” It means “this feels worth 3-10 hours of my life.” You’re betting that learning more will be valuable, regardless of outcome. You’re not pitching investors. You’re deciding whether to open a notebook and write some code.

How do you recognize genuine excitement versus wishful thinking?

Genuine excitement looks like: thinking about it in the shower, getting curious about edge cases, being okay if it “fails” as long as you get to tinker. Wishful thinking looks like: being more excited about how it will look on Twitter than about building it, needing others to be excited first, imagining skipping straight to success.

Protect nascent ideas from premature criticism. Give yourself a protected window, even just 2-4 hours, where the only question is “what can I learn?” Use low-stakes artifacts: a scratchpad, a throwaway repo, a single notebook.

Don’t ask “is this a good startup?” Ask “is there something interesting hiding here?”

AI Interpretability as a Thinking Tool

In machine learning, interpretability means techniques to see how models represent and manipulate concepts: attention visualizations, activation probing, saliency maps. These are ways of asking: what features does the model consider important, and how are they organized?

Here’s the metaphor that clicked for me: your idea is like a latent space. It’s not one bullet point. It’s a cluster of related concepts and hunches. Interpretability techniques show how models cluster and relate concepts, and you can steal those lenses for your own thinking.

Some practical lenses to borrow:

Feature breakdown: What are the underlying dimensions of this idea? (Who, what, when, failure cases, edge users.)

Counterfactuals: What would need to change in the world for this idea to be clearly good or clearly bad?

Probing: Ask specific questions about different aspects. Does this help beginners? Experts? Offline users?

Near/far examples: What ideas or products are nearby in concept space? Which are deliberately far?

Here’s a concrete technique: describe a handful of related ideas or problem statements to an LLM and ask it to group them by similarity. You’ll notice things like “I’m actually thinking about two different ideas here” or “there’s a gap in this space I haven’t explored.”

Another technique: saliency-style questioning. Given a rough problem description, ask the LLM to highlight which parts seem most important, and why. This forces you to see which components you’re implicitly weighting. Try a prompt like: “Extract the 3-5 most important phrases that determine whether this idea succeeds. For each, rate the user impact and the build risk.”

The key insight: you’re not trusting the model’s worldview as truth. You’re using it as a mirror to surface assumptions and blind spots in your own thinking.

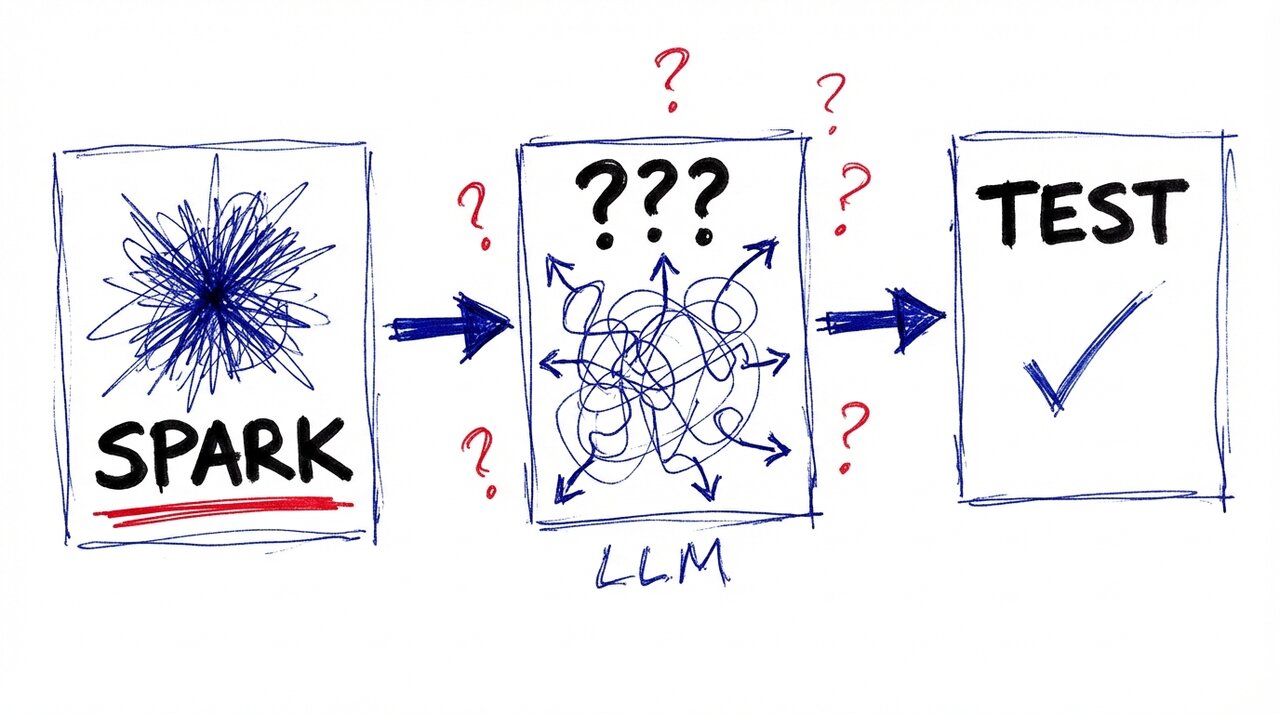

LLMs as Exploration Accelerators

The default way to use an LLM is “give me the answer.” For exploration, you want the opposite: “show me interesting options.” You’re aiming for breadth and surprise, not correctness or polish.

Prompt for divergence. Ask for multiple distinct directions. Force variety by adding constraints: one for beginners, one for experts, one hardware-heavy, one browser-only. Encourage the model to disagree with itself. Try something like: “Generate 8 significantly different variants of this idea. For each, change the target user, the environment, or the primary value proposition.”

Borrow from other domains. LLMs have read about physics, biology, cities, and supply chains. When you place your idea next to concepts from those fields, you nudge the model to map structure instead of repeating familiar product patterns. You’re asking it “what does this look like if I treat it as a different kind of system?”

Try prompting directly into that: “Here is my idea: [2 sentence summary]. Treat it as if it were a biological system. Identify the ‘cells’, the ‘organs’, and the feedback signals. Then propose 5 variants of the idea that borrow from how real biological systems stay stable or adapt.”

Or mix a few domains in one shot: “Here is my idea. Compare it to: 1) a physical system with forces and constraints, 2) a city with neighborhoods and infrastructure, 3) a neural circuit with signals and noise. For each analogy, point out structures I’m missing, likely failure modes, and one surprising variant suggested by that analogy.”

Pick domains where you have at least a bit of intuition so you can tell which parallels feel useful. The goal is not to force a perfect metaphor. You’re using cross-domain structure to surface constraints, edges, and alternate shapes your idea could take.

Avoid premature convergence. Don’t let the model jump to “the best” idea on the first pass. Run early passes with rules like “no evaluation, only generation,” then a second pass that ranks. Maintain a scratchpad of ideas you’ve parked but haven’t killed.

A two-phase approach works well:

-

Divergence phase: “Generate 12 diverse variants of this idea. No evaluation yet. At least 3 should be weird or non-obvious. Don’t say which ones are good or bad.”

-

Convergence phase: “Here are my 12 variants. Now select the 3 best suited for a solo engineer with only weekends available and no budget for infrastructure. For each, propose a 2-hour experiment to test whether it’s interesting.”

Use temperature and randomness intentionally. If your LLM has a temperature or creativity setting, turn it up for early exploration. Higher temperature encourages weirder outputs. Early stage equals high randomness; later equals refinement.

A Lightweight Exploration Process

With these tools, you can spin up dozens of directions in an afternoon. The question becomes: how do you turn that messy cloud into one testable step?

Here’s a simple loop you can run in 1-3 hours:

Step 1: Capture the spark. Write 1-2 sentences on what excites you and why. Capture images, analogies, mental pictures. Don’t worry about correctness. Pin the feeling to text.

Step 2: Expand the space. Use an LLM to generate variants, edge cases, alternative users. Apply interpretability lenses: feature breakdown, counterfactuals, near/far analogies. Optionally ask the model to cluster a handful of variants to see if you’re mixing multiple ideas.

Step 3: Down-select with constraints. Introduce your real constraints: available time, skills, hardware, APIs. Ask which 1-2 variants you’re most curious about and can prototype cheaply. Keep a backlog of promising-but-not-now ideas.

Step 4: Design a tiny experiment. A 50-line script. A notebook with 3 non-trivial examples. A single UI mock with 3 clickable interactions. Define success criteria before you run it: what outcome would make you say “this is worth a weekend”?

Step 5: Run, observe, log. Actually run the experiment. Log what surprised you, what felt harder or easier than expected, whether your excitement went up or down. Treat this as data about you, not just about the idea.

Step 6: Decide next move. If excitement plus signal went up, plan the next slightly bigger experiment. If it flatlined, archive your notes. It’s experience for future intuition. If you’re unsure, get 1-2 targeted opinions by showing the artifact, not a pitch deck.

When should you trust intuition versus seek feedback? Trust intuition for whether you enjoy working on this and whether learning feels compounding. Seek feedback when you’re about to commit serious time or money, or when you’re confused after a couple of experiments.

Start Before You’re Ready

You don’t need a grand vision or a 10-year roadmap to begin exploring. You need a hunch, a couple of hours, and a few simple tools: your own curiosity, a notebook, and an AI assistant that can help you see your ideas from new angles.

Treat exploration as a craft. Treat prompting as an art form. Try things. Rephrase. Ask the same question five different ways. You can always undo and try again. Ship more weird experiments. Build better intuition. Give your best ideas a real chance to grow.

The starting line will always feel uncertain. That’s not a bug. That’s where all the interesting work begins.